Granite again? Well, yes, and when I think about it, I hear the Eagles enthusiastically singing “Take it to the limit. One more time.” This last hike was my thirteenth time (actually 13 ½ if you count that ignominious episode when I got caught out in a downpour halfway up and without rainwear). Probably a modest number of ascents when compared to others, but a baker’s dozen is nonetheless a magic number.

I remember a year's earlier ascent in late June. We experienced a brilliant sunny day with wildflowers blooming, including a profusion of lupine, Indian paintbrush, columbine, and Beargrass blossoms. And, once past the high-angled meadows, we encountered the first snow fields and the trail became indistinct. Once at the steep ridge to the fire lookout, we had the choice of scrambling up through a jagged jumble of granite blocks or taking the snowfield. We opted for the granite and soon regrated that decision. While the upper granite near the lookout has more flat blocks and is easily navigable the lower sections are a mess of large sharp blocks jutting every which way with no obvious clear path other than up. It was hugely frustrating, consuming lots of time, and we almost bailed on the hike. “You know we don’t have to go to the top.” “I know.” Having acknowledged that, we then kept on up the granite for a bit longer and then stepped off to the snowfields, kicked steps, and continued up. It was a glorious sunny day with Mt. Rainier and Mt. Stuart clearly visible. We spent about half an hour having lunch and visiting with other hikers at the historic lookout. A day to remember.

Another memorable trip was the result of my fascination with night sky photography. I was looking for dark sky photo opportunities and conceived a Granite Mountain Galaxy Quest to achieve the photographic equivalent of a first ascent. Being familiar with the site, having hiked to it several times before, I previsualized the composition with the relative positions of the fire lookout, Mount Rainier, and the Galactic Core. Then, I contacted some friends to share the adventure with and we waited for the right conditions to come together.

Mark and Chase jumped at the chance when I invited them to join me on a hike up Granite Mountain to photograph the Galactic Core of the Milky Way. Then we hiked. Packing photo gear and overnight kit up 3,820 vertical feet was brutal but soon forgotten as we dined on Mark’s scratch-made smoked turkey sausage camp stew and settled in for the light show. I worked the camera into the dark as the GC appeared in the southern skies over Mt. Rainier.

There was no campground. It was a bivouac situation. We needed to shoot late into the night sky and then either hike out in the dark with headlamps after the shoot or pack sleeping bags and pads and bivy until dawn and then hike out in the daylight. Because of the potential for injury hiking out in the dark on this trail we elected to bivy. I got 3, maybe 4 hours of sleep, but it was worth it!

Waking at dawn, we reluctantly packed up and hiked down from the site of the night sky magic. We counted 102 people coming up Sunday morning as we descended (even before the Pratt Lake Trail intersection). Party up top! We decided to award a mini chocolate bar to number 100 and since the universe is a strange place, number 100 was a woman who Mark had worked with at K2. Of course, Diane was delighted with the chocolate prize and seeing her old friend Mark again. Really. You can't make this stuff up. Trip verdict? Priceless!!!

I

have reflected that the hikes to Granite Mountain Lookout are always a standout

experience as the changing seasons offer a continuing opportunity to experience

the scenery in new and ever-fascinating ways. The hike is at once both comfortingly familiar and yet intriguingly new, like

reconnecting with a long-lost old friend.

So

why was I now hiking it again? It was both the lure of fall color and the need for wooden

shingles. The Snoqualmie Fire Lookouts Association was seeking volunteers to

carry wood shingles up to the lookout for a roof repair (after last week's llamas

flamed out after a mile last week). I almost went for the llamas, but didn’t.

Who wants to be stuck behind a pack train for four miles, no matter how cute

the animal? I would wait. And now, while I equivocated about the possibility of

being part of a conga line of happy hikers with shingles (wood shingles), I

decided to be a part of it. It was an opportunity to give back and maybe meet

some fun people.

I

snagged one of the last parking spaces in the lot at 7:40 am, and after some

milling around as folks unloaded the shingle packets from a truck, I moseyed

up, signed the register, and picked a bundle. I found a medium-sized packet that

slid snugly into my 50-liter pack. There were no coffee gift cards. But they

did have homemade chocolate chip cookies, which I forgot to sample. I just

wanted to get going in the cool of the morning, before the inevitable heat that would come later in the day.

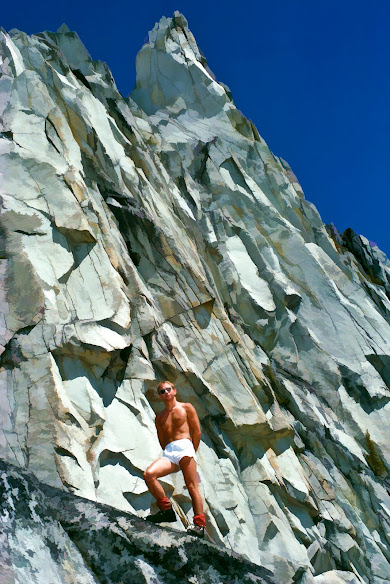

The first two miles of the trail in the shady wooded section were the usual study in browns and greens, almost monochrome. The dusty trail snaked up the mountain meandering through ever-steeper rocky sections. The first mile is easy and then, after the trail split, the rocky route gets down to business. This is the section where I’m still warming up and I’m asking myself why I ever thought this was a good idea. Why indeed? Well, it’s for those gorgeous upper mountain meadows that are festooned with Beargrass blossoms in the early season and aflame with color in the fall. It always takes my breath away.

I was

surprised that there was no conga line and not surprised that I met some

interesting fellow hikers. After breaking out of the woods, I made my way up

through the meadows, which I regard as the best part of the hike. The arduous earlier

ascent would be behind, and while there is still much elevation to be gained, it’s

far more pleasurable. Yes, the trail is still chockablock with boulders but this

section flows upward, and I feel as if I am dancing with granite, as the sheer

magic of the hike reveals itself. This is the place where you can go faster but

you are best served if you slow down and let the magnificent scenery just wash

over you. Today we hiked through a heart-stopping visual symphony of fall

color. I could hear Wagner’s dramatic operatic ‘Flight of the Valkyries.’ I

didn’t want it to end, and yet we had more work to do.

We

continued on the summer route to avoid the boulder-strewn ridgeline and

ascended the tedious backside switchbacks up to the final rocky ramp to the

iconic Granite Mountain Lookout. Always a visual treat!

After handing off our shingle packets, which were immediately taken up into the lookout, we found places to sit and refuel. Even after hiking slowly with frequent pauses to sip water, I was surprised to note that I had arrived in 3 hours and 15 minutes. It felt slower than that, more like four hours. By now it was quite warm and the skies were clear for miles, four volcanoes visible from the lookout. Even Mt. Stuart made an appearance. The vibe was friendly and festive, with groups of hikers savoring the day. I felt suspended in time as Elizabeth made a summit espresso which she drank from a tiny stainless cup, the silhouette of mighty Mt. Rainier visible in the background as thin clouds streaked across the horizon. What a day! This is why we do it.

As I descended, I encountered many more shingle-laden hikers on the way up, some complaining about the strenuousness of the hike. Hey, as one seasoned hiker observed in a trip report from long ago, “No matter how fit you are, Granite always kicks your butt.” Why is it so I asked myself? I think it goes beyond mere stats of mileage and elevation gain as it is, often, an obstacle course of granite that makes you work harder for each step than you’d ever expect. Of course, one can always aspire to dance with the granite. I like to imagine that on my best days that I am dancing, flowing like water, upward through the boulders up to the historic fire lookout, the visual epicenter of my quest. Visualization is, I think, so important as we disappear into the mystic.

I confess that I took no heavy camera gear on this last ascent as the shingles were enough. In the past, I have hauled my serious camera and tripod up and made several spherical panoramas from the summit. But in case you are interested, I took a spherical panorama on Sept 12, 2019, that shows what the summit looks like on a sunny cloud-filled day without the snow on the ridgeline. A day much like today. And I include the link to one I took the morning after our 'Granite Mountain Galaxy Quest.'

For best viewing click on the ‘Toggle Fullscreen’ icon in the panel in the upper right of the onscreen image. Then scroll to experience the immersive image. I have many other spherical panoramas from wilderness adventures that are hosted in my portfolio at 360Cities.net. And, there are several more on Granite Mountain. Just Feel free to look around.

Granite

Mountain, Summit Friends, Alpine Lakes Wilderness: https://www.360cities.net/image/granite-mountain-summit-friends-alpine-lakes-wilderness-washington-state

Granite

Mountain, Dawn Patrol, Alpine Lakes Wilderness: https://www.360cities.net/image/granite-mountain-dawn-patrol-alpine-lakes-wilderness-washington-state-usa