They appeared as ants, dark specs moving slowly up the immense granite walls of the 3,000-foot rock monolith. The dominating visage of El Capitan was stunning to us, as were the tiny forms of the climbers. We stared at them, as did others, at their systematic, incremental progress toward the top. I was captivated and puzzled. Not content to merely look, I asked myself, “How do they do it?” It was a potentially dangerous question to ask. It could lead to learning the ‘how’ and then rapidly progressing to the ‘doing’ of climbing, an enterprise not without risk.

I held that curious question in mind

as we entered the weathered wood structure that housed the Curry Company, the sole

outfitter's store in the valley at that time. We added some trail treats to our

basket and headed to the wood-planked sales counter. I noticed a small sign

next to the ‘Pack It In, Pack It Out’ stickers. It said, ‘Go Climb a Rock.’ It

advertised a two-day course in rock climbing instruction for beginners, to be

conducted on the rock escarpments little more than a stone’s throw away from

the Curry Company store. The price was affordable, and the climbing gear would

be provided. I reread the words, decided for myself, and turned to my

girlfriend Lara, my sales pitch short and to the point.

“We’re here, and we’ve got the time. Let’s do it.” I said as purposefully as I could. Adventure girl that she was, Lara readily agreed. We signed up on the spot.

And with that, I took what would be my

first adventurous plunge into one of the oldest of alpine sports, technical

climbing on rock, snow, and ice, the mediums of mountaineering. Climbing soon became

my all-consuming passion, an infatuation, an ardent love affair with the spiky

peaks and their magnificent wilderness environs. My immersive romance lasted

through the years of my youth, until I met that special woman, married, and

became a father. I then took a break from alpinism, finally admitting that it

was a pursuit not without serious risks and the real possibility of death.

Nevertheless, over the years, the

mountains have continued to call and I still journey forth to be a part of

their magic and light. I mention my earlier obsession because my current quest

with spherical mountain photography is the result of my insatiably curious mind

and the same basic question. When I first encountered a 360° panorama I was

awestruck. And so again, I asked myself, “How do they do it?”

It has been over 10 years now and most of the practitioners of this curious pursuit still reside in Europe. The preeminent 360 media agency that hosts my images is located in Prague, and Elena, my primary contact, lives in Madrid. To be fair, there are serious and very talented 360° photographers in the states, but there are not many. They are outliers. And, most do not want to pack their heavy photo gear high into the mountains. So, many of the locations I photograph in the mountains are the photographic equivalent of 1st ascents, at least in the realm of 360° panoramic photography.

I

hear it more often than you might think. After viewing one of my immersive

spherical panoramic images, most viewers are somewhat impressed and yet have no

idea what is involved. That is especially true if they experience the photo

rotating on my cell phone. They’ll often look at me and say, “What kind of app

is that?” or “You must have a good camera.” That default compliment has always

puzzled me. I usually just reply that it is not an app and yes, I have a good

camera. Why? Because I know their words are well-intentioned, and any further

explanation would probably soon have them rolling their eyes, drifting off, and

looking to get rid of me.

What? You say you are interested? Seriously? Okay then, here is the ‘inside baseball’ on how I make spherical panoramic images.

As

with any photographic subject, one should previsualize the result and seek out

the right location, composition, and time of day for optimal lighting. Barring

that, you can just impulsively wing it if you see something worthy. No matter

the situation, it is critical to achieve a heightened awareness of your

surroundings and to note what is static and what is moving so you can adjust accordingly. Though

some smartphone apps and dedicated 360° cameras can take a 360° image, none

provide high-resolution images with high dynamic range or produce a complete

photosphere without some artifact in the ground portion (which I don’t want to

see). After all, I am a purist.

So, what’s my process? The approach that I use involves stitching together multiple individual images to complete the full spherical image. I compose my scene, dial in my exposure settings, set up my tripod, level my panoramic camera head, and take eight bracketed sets of perimeter images, every 45 degrees, then a vertical shot (or more than one), two down photos with the tripod, 180 degrees apart, and finally additional down shots with the camera tilted over where the tripod was previously positioned.

Why?

Because I use those images in Photoshop to create layer masks to eliminate the

tripod and any attendant shadows from the down shot. I often take additional

safety shots of the perimeter if I have obvious moving objects like people, wind-blown trees, and clouds. Any movement will have to be de-ghosted from bracketed images in post-processing. And, I use radio triggers to actuate the shutter to avoid camera

movement. That also allows me to step back and keep my shadow out of any

images. It is especially helpful in precarious places (think sketchy mountainous

situations with loose rocks and sheer precipices).

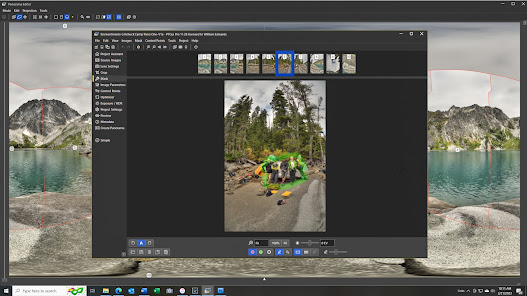

I take three exposures of every image, bracketing plus and minus two exposure values to create a range of exposures that will reveal both shadow and highlight detail. These three bracketed images are then tone-mapped in Photomatix to create one high dynamic range image. I upload all HDR images into Lightroom and make my final selections. Selected images are then processed in Photomatix to merge the bracketed images and create tone-mapped composite HDR (high dynamic range) images. Once I have Photoshopped the tripod from the down shot images, I load the selected eight perimeter images, the overhead image, and the edited down shot into a Dutch software program, PTGui, to stitch the 10 images together into a seamless flat equirectangular image suitable for panoramic viewing software.

Prior

to the final output, PTGui allows for image masking, adjustment of stitching lines,

and final image orientation. Every stitch line is examined with a virtual

magnifying glass to make sure there are no parallax errors where things don't line up The final stitched image

is then exported as a large Photoshop file with all individual layers and the

composited final image. After the final layer mask adjustments, the Photoshop file

is flattened and saved as a Tif file. The Tif file is uploaded to Lightroom for

the addition of metadata such as copyright and keywords. Once final exposure and

other tweaks are made the equirectangular image is exported to a desktop folder

as a Jpeg.

PTGui

is used one more time to create a QuickTime file from the Jpeg so the panorama

can be viewed by scrolling on the desktop for a final quality control check. At

this stage, I often discover something that eluded me earlier and I can go back

to the appropriate place in the process to make the necessary adjustments.

The final step is writing the descriptive copy and uploading the image, keywords, copy, and location data to 360Cities.net which will host my image and make it accessible to anyone via the assigned URL. Sometimes 360Cities.net will award me an ‘Editor’s Pick’ which is always gratifying as it offers featured exposure on their site. If I am happy with the results, I tell my friends. Then I am on to envisioning my next subjects.

How long does it take? Well, the fieldwork often involves hours of driving and then hiking into a remote location. I do not count that time as photography is often only part of the reason for the journey. Once on-site. it takes a few minutes to evaluate the subject and adjust exposure settings. After the camera is on the tripod all exposures are created in about two minutes. Post-processing is where the time gets chewed up. It used to take roughly four hours to process a panorama on my old computer but after I built a new computer with a faster CPU, it now takes around an hour, if there are no glitches. Workflow is important and after creating over 500 spherical panoramas, I know what I am doing. Although I am always humbled as I learn something new each time, mostly in the field. Is it worth it? For the right subject, absolutely! I find there is something magical about both the process and the result. Somehow, I never tire of revisiting my panoramas on 360Cites to scroll around and to virtually be in those special places once again.

Here are links to the panorama I took from the Red Pass images with me and my camera setup, and an example that I took of a group of us camping at Colchuck Lake in late September 2019. For best viewing roll over the image and click on the ‘Toggle Fullscreen’ icon in the panel in the upper right of the onscreen photograph. Then scroll to experience the immersive image.

Red Pass Vista with Peaks, Alpine Lakes Wilderness, WA State: https://www.360cities.net/image/red-pass-vista-with-peaks-alpine-lakes-wilderness-wa-state

Colchuck Lake, Alpine Friends, Alpine Lakes Wilderness, WA: https://www.360cities.net/image/colchuck-lake-alpine-friends-alpine-lakes-wilderness-washington-state

No comments:

Post a Comment